Did you battle intestinal parasites with the goats, sheep, or camelids on your farm this year? We only tend to think about parasites in the warm season when the diarrhea is plentiful, the eyelids are pale, the hair coat looks terrible, the weight withers away, or the appetite diminishes. Winter is one of our very best times to strategize for warmer weather, a time to get a handle on your herd’s worm burden before the numbers are out of control in warmer weather.

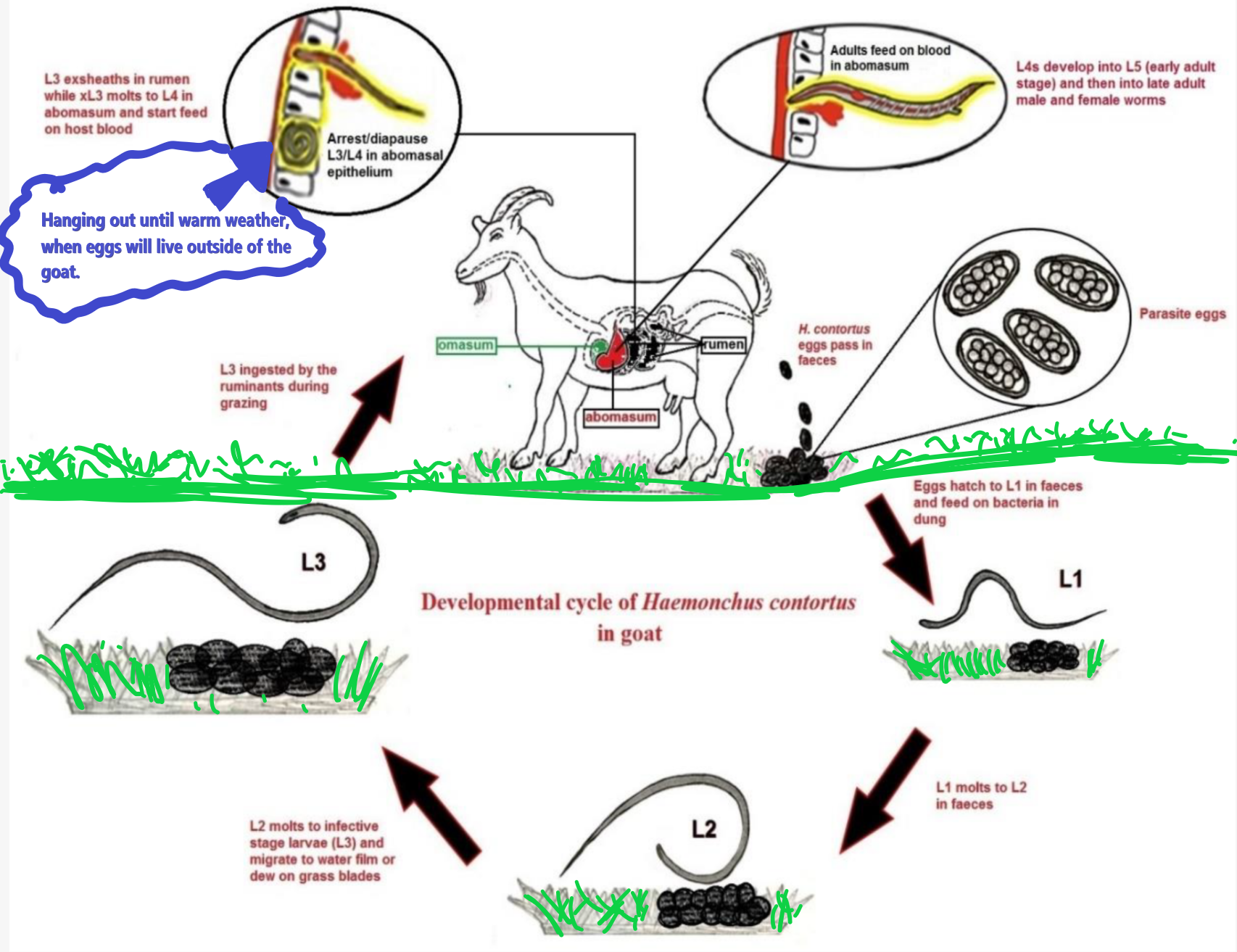

Time and time again we hear, “it came out of nowhere.” Here in the Southeast United States, we are largely talking about the barber pole worm (haemonchus contortus), those “strongyle-type” eggs you see on the fecal egg counts you get from our lab reports. One adult female barber-pole worm living in your goat, sheep, or camelid can lay 5,000+ eggs in one day! Three weeks later, each of those eggs that become females will be mature adults making their own eggs, 5,000+ eggs each, per day! It just does not take long for things to get ugly. We need to look at how the enemy works to plan the battle.

Important points:

- Adult worms (sometimes called L5 larvae) live in the animal’s gastrointestinal tract.

- Adult worms pass eggs into the animal’s feces to contaminate your pastures.

- Animals become infected by eating an infective-stage/”L3″ larvae.

- L3 larvae can either mature into a blood-sucking L4 larvae and start feeding through the abomasal (“stomach”) wall, causing anemia, diarrhea, weight loss, protein loss, bottle-jaw, and all the signs of worms you are accustomed to; OR

- The L3/L4 immature larvae can ARREST its development in the lining of the abomasum. That’s right, it can dig into the stomach wall and HIBERNATE there all winter long. This is how worms survive the winter, their secret weapon. They do not suck blood when arrested and we will not see eggs on a fecal egg count because they are not actively reproducing, but they are still in there! Because their eggs struggle to survive and mature on your pastures during the cold winter, they have adapted to hibernate in the animal until warmer weather supports a better opportunity for them to reproduce and reinfect.

We can use this information to help us battle the worm. Knowing that very few eggs can survive out on winter pasture, if we can enter the winter with very few worms “hibernating” in our animals, then can set ourselves up for starting the spring grazing season with far fewer worms. In some cases, following a difficult worm season, we will advise clients to deworm with a drug that will kill the arrested L3/L4 just prior to winter or just prior to grass starting to grow in the spring. This will help us start spring with lower pasture loads and then implement our grazing season plans for management.

REFUGIA

Another important tool that is overlooked is the idea of “refugia”. Refugia refers to the worms or eggs in the population that are still sensitive to dewormers. Think with me. If we deworm an entire herd of goats, we might expect to kill 95% of the adult worms they have in their GI tracts. Now remember, those adult worms have been making eggs that are out there on the pasture. Those eggs out there carry similar genetics to those 95% of adults we killed. So here is the question people ask:

- DO we move the goats into a new pasture?

- DO we leave them in the same pasture for some time?

LEAVE the animals in the same pasture! Let them reinfect themselves with the eggs of those worms we just killed. We know those eggs will mature into adults that will carry similar genetics and we can likely kill them with our same dewormers. Worms mate with one another to create offspring – we want that wormy gene pool loaded with dewormer-sensitive genetics to dilute out the resistant worms. If we deworm our animals and move them directly into a clean pasture, they will be shedding resistant eggs, reinfecting themselves with mature worms that we likely will not be able to kill with the same dewormer.

Instead of deworming the whole herd, the preferred strategy is to selectively deworm only the anemic and immunologically weakest of animals, or those with a lab-confirmed high worm load, then move the entire herd into a “clean” field. Females nearing birth or in the 2 weeks following birth will carry higher worm loads as their immune system is compromised. Young animals under 12 months of age also have a challenged immune system and are higher risk of fatal infestation. We know that there are animals carrying smaller numbers of worms that are just not making them sick, and we do not want to deworm those animals. We allow them to move with the animals we deworm onto a new field where they will spread those sensitive worm eggs on the new field – eggs that will develop into adults that will be sensitive to our dewormer in the future.

WE MUST MINIMIZE the number of animals we are deworming and how often we are deworming. Each time we grab a dewormer and expose worms to it, we are leaving behind resistant worms that we have to manage. Research has shown that resistance develops much slower if we use two different drug classes of dewormer at the same time. Your veterinarian will help you pick the right combination that is safe for animals in regards to the animal’s weight and reproductive status.

OTHER STRATEGIES

We know it takes 3-4 days for an immature worm passed in fresh feces to be come an infective L3 worm that an animal can ingest and become infected. We can rotate pastures with animals carrying low worm-loads using strip grazing and similar strategies every 3 days to minimize reinfection.

Other strategies like feeding high-tannin forages, such as Lespedeza will keep adult worm numbers lower, minimizing the numbers we are fighting. We can also administer low doses of encapsulated copper oxide wire particles periodically to kill adult worms.

A recently released product Livamol with Bioworma is available to mix into an animal’s diet. The product passes through the manure and actually kills infective L3 larvae on the manure pile, preventing it from developing. It is not a dewormer – it will not kill the adult worms that are harming your animal. It should be used after deworming.

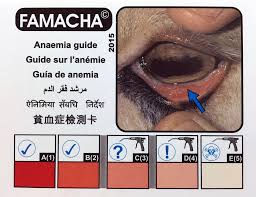

There is just more to it than deworming. It is completely different than dogs or cats. The worm is different, it is highly prone to developing dewormer resistance, it reproduces at an unbelievable rate, consumes an alarming amount of blood, and it exists on the animals food – GRASS. This is a hard concept for new goat, sheep, and camelid owners to grasp as most animal lovers started with a dog or a cat. We want every owner to feel comfortable looking at their animal’s eyelids to judge their level of anemia using the FAMACHA system. Our team is dedicated to helping you succeed with managing your herds and flocks. We commit to staying up to date on best practices and making sure that those are communicated to you so we can reach our goals – whether that is food or fiber production, or a long and happy life as a companion.

Phone: (828) 738-3883 | Fax: (828) 270-3213 Email:

Phone: (828) 738-3883 | Fax: (828) 270-3213 Email: